by Maia Brown, Infant-Toddler Education Teacher

A number of years ago now, teaching at an early childhood center in North Seattle, my class of four and five-year olds began writing songs. None of us could ever seem to remember how it really started.

We had a long-standing tradition in our classroom of Story Table. Inspired, in part, by educator and early learning theorist Vivian Paley, a table in our classroom would transform into a drop-in storytelling podcast of sorts. Children would see the Story Table sign come out and would arrive with stories to tell and sign up on a guest list to get the floor. Teachers sat ready to transcribe those stories word-for-word. Stories would be read back to the author for approval and for the great pleasure of hearing your own words in the mouth of your teacher and your peers relishing the repetition of your yarn. Later, teachers typed up the stories, and children would revisit them, adding illustrations or having them read aloud ritually at Circle.

Some cohorts gravitated towards more collaborative storytelling at Story Table or Circle. The year we started writing songs was certainly one of those years. Watching children build a story together was like watching the baton pass in a relay. It was not always effortless, but sometimes it had the practiced grace of an Olympic team.

This may be one of the origins of our song writing. At some point someone announced that they were writing a song and not a story. As teachers, we began to wonder together what made a song different from a story. We waited to find out. We quickly discovered that children had a strong sense of the genre. They really were becoming lyricists. When a collective song-writing session would be requested, we often asked “what is this song called?” Starting with the title didn’t function to make the process artificially linear, rather it was key for a collective process. It is what announced a theme or starting point so that it was easy for everyone to jump in with lyrics and not be told by others that it didn’t fit the song. Then we would ask, “So, how does it start?” It was like an improv game as we waited for someone to be our first instigator. We would ask, “what’s next?” as an invitation to others. We would ask, “Is that the end? How does it end?”

This tradition of prompting developed spontaneously, instead of “going around”–having a teacher dictate how different children’s voices should contribute to the collective–different folks responded to the call or the wondering. Both teachers and children initiated these questions and took on the role of facilitator. This meant that song-writing sessions were not about making your voice heard in particular, but the excitement to know how others would pick up where you had left off. Each lyric became a cliff hanger for the rest of us as someone else jumped in.

Later in the year, smaller collaborations began to emerge during the day, duos or groups of three would request transcription services from a teacher as they composed a song. As well, a number of children became regular solo writers. All of these songs were typed and collected. What was particularly remarkable for teachers initially was that this process did not yield unstructured “stream of consciousness” word collages as one might have imagined. Songs quickly took on familiar forms—repetitions and variations on themes that often began to emerge as verses and choruses.

We wanted children to know how exciting we found their work, we wanted them to know we took them seriously, that we saw them as songwriters. And we wanted to hear these songs! So, we called in collaborators. We started sending our lyrics to local bands and solo artists. They were friends and friends of friends. Eventually there was a grapevine, and some folks came to us wanting to be roped in!

We had a process for inviting musicians into relationship with us. As a new song was coming together in our class we would ask the writers if this was a song they wanted to send to an artist. If children deemed a song worth sharing, we would sit down together and introduce the musicians available to collaborate. We would talk about what we knew about them and then play clips of their work from Bandcamp pages and websites. Often we would have multiple songs we were matchmaking. Does this feel like a folk-punk tune or a pop-rock kinda song? Children had pretty clear feelings about who would be the best home for a particular song after exploring different artists’ discography.

And then we would wait.

The first song we got back from a musician was exhilarating. As teachers we wondered how the children would respond. Would it feel like it was still theirs? Would they enjoy it but find it hard to connect what it felt like to write it with what it was like to hear it? We turned the volume up to find out. It was as if the song that folk-punk soloist, Marc Ball, sent us had always been the song. It was magic. It was like an old friend coming home to visit. Everyone was almost nonchalant in their approval: “Yeah, that’s how it was supposed to sound.” Soon we were all singing our songs as we went about the day!

When musicians added melodies, rhythms, and syncopation, the words met the music and the process created its own logics. The lyrics became songs, full of their own magical sense-making. Universally, the musicians we ended up working with were both charmed and impressed. Many had initially assumed that they might need to play around with the lyrics they got. What they received, however, were fully-formed songs with places for recurring melodies, moments for musical escalations or crescendos–they had shape and musical cues. In fact, our only request and direction for artists was that the lyrics would not be changed and that they engage in their usual process for working-up a song.

To us, this didn’t sound like “kids music,” but songs solidly within each artist’s own musical traditions and temperaments. And we could hear how much fun folks are having! Some musicians described themselves finding new energy to write their own music after working on one of our preschool tunes. Some bands we worked with began playing our songs at shows. This was a kind of intergenerational praxis that got everyone playing–in every sense of the word.

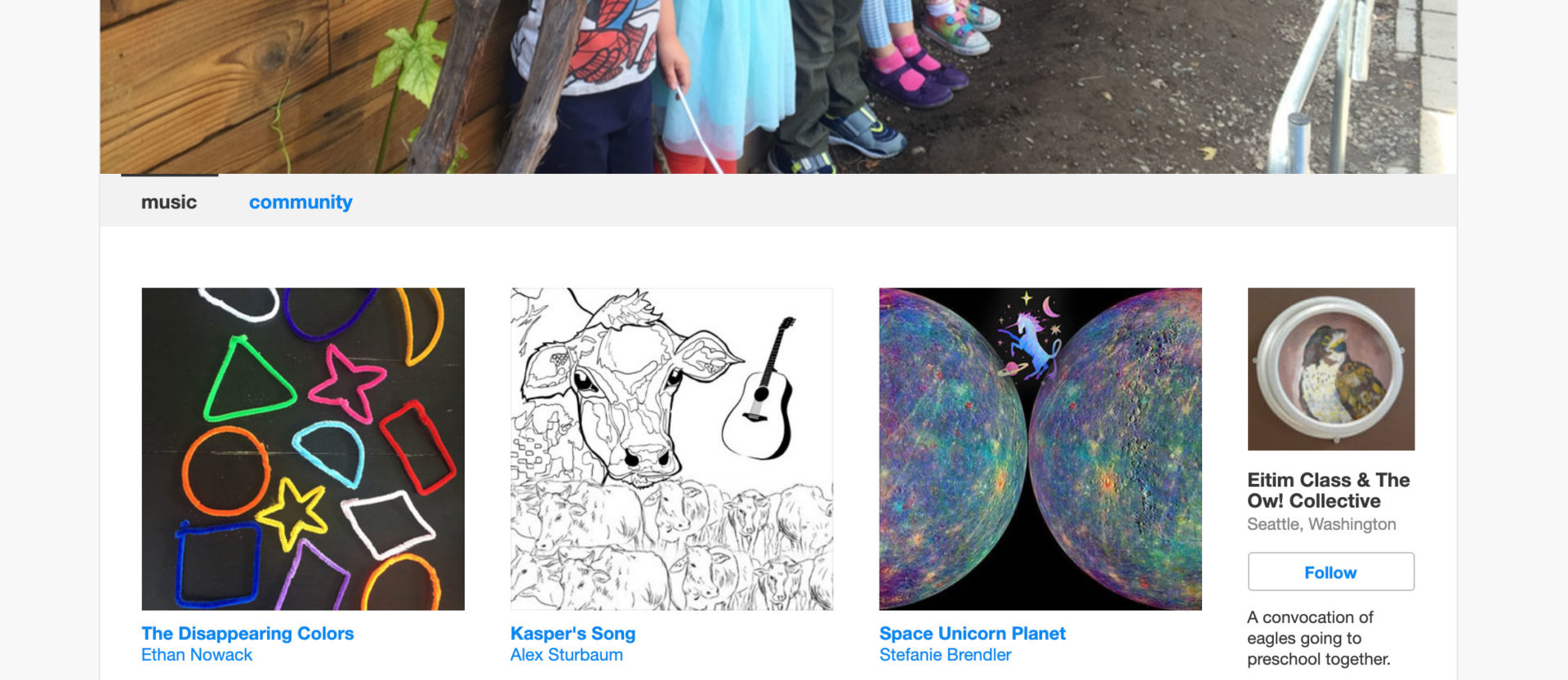

When we decided to share our collaborations more widely we set up a Bandcamp site—dubbing the project, ow!tunes—for free download with an option for donations. We started getting money from friends, family, and strangers. Another Circle was in order. We sat down to talk about where the money should go. Children had recently been asking for more resources to understand homelessness in our community. It was a crisis they saw everyday as they drove or bused to school or played in local parks where folks were camping. My co-teacher had experienced homelessness as a young person and was able to tell stories throughout the year that helped us understand together the stories that children were seeing glimpses of in their daily lives. One organization that had been important for my co-teacher during that time in their life was PSKS—Peace for the Streets by Kids from the Streets. Our class decided that any money that people paid for their songs should to go to kids at PSKS. PSKS has since had to close its doors, but ow!tunes is still free to download and now comprises two albums of music and a few singles. Check it out here.